- AOLF Important News

Privatization of the Roads, Oceans, and Outer Space – Dr. Walter Block at Liberty on the Rocks – Sedona

- By webmaster

Featured

Categories

- “Government” 5th Edition

- AOLF Important News

- Censorship

- Controlled Opposition Watch

- Controlled Perception

- COVID

- Covid Investigation

- Economics

- Eugenics Investigation

- Events

- Evidence of “Gov’t” Criminality

- Fact Check

- False Flag Attacks

- Five Meme Friday

- Free State Project

- Government Criminality

- Government Indoctrination

- Interviews

- Investigations

- Liberty on the Rocks

- Monopolization

- News

- Press Release

- Publications

- Speeches and Talks

- Truth Music

- Updates

- Voluntaryism

- White Rose Mucho Grande

- Uncategorized

Our purpose:

The Art of Liberty Foundation (AoLF) focuses on exposing the integrated, criminal control of government and media while providing rational and moral alternatives via voluntary interaction through free markets, decentralized trade, and communication.

Who we are:

A start-up public policy organization: Voluntaryist crime fighters exposing inter-generational organized crime’s control of the “government,” media and academia. The foundation is the publisher of “Government” – The Biggest Scam in History… Exposed! , and its companion media: The Liberator– our expose of “government” illegitimacy and criminality, ArtOfLiberty.Substack.com – our original writings and research, The Daily News – a curated feed of the best of the alternative media, censored truth videos, and more on Substack and Telegram, Five Meme Friday – a lower volume weekly summary of the Daily News and at least five fresh, hot, dank liberty memes on Substack and Telegram, and “Government,” Media, and Academia Exposed! – A Telegram summary of the best mainstream and alternative news stories proving our thesis that all three are being hierarchically controlled by inter-generational organized crime interests.

AOLF Important News

The Daily News

The Daily News from the Art of Liberty Foundation

The Daily News from the Art of Liberty Foundation

- DOJ Reveals Potential Epstein Co-Conspirators. Internet Reveals Other Epsten Email Authors. February 11, 2026

- Is Brain Rot Real? Researchers Warn of Emerging Risks Tied to Short-Form Video February 11, 2026

- Unfit People Face 775% Higher Risk Of Blowing Their Top From Stressful Moments February 11, 2026

- How Men Choose Women February 11, 2026

- Trump cabinet member ensnared in Epstein scandal February 11, 2026

- FiveMemeFri-The Great Taking - You Don't Own Your Stocks The Way You Think You Do! February 11, 2026

Dr. Walter Block, the guy who WROTE THE BOOK on privatizing roads and highways, explains who would build the roads at The Voluntaryism Conference in Sedona.

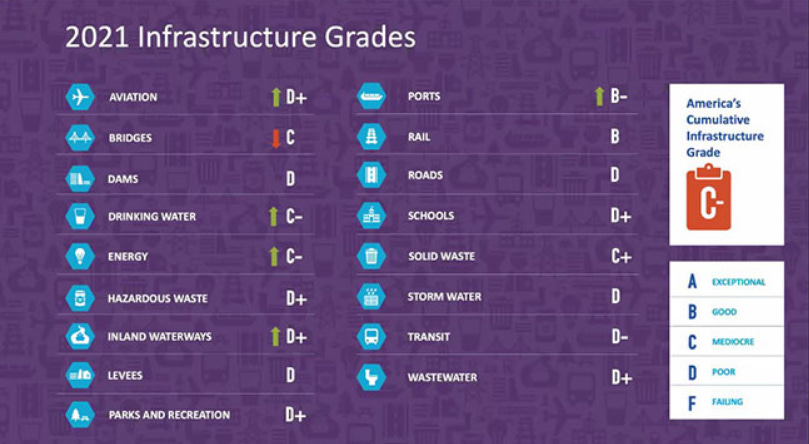

In this, the 7th episode from Liberty on the Rocks – Sedona – The Voluntaryism Conference, renowned economist Dr. Walter Block delves into a classic libertarian question: “Without government, who will build the roads?” The transcript below is illustrated with memes and visualizations from Etienne de la Boetie 2’s upcoming book: Voluntaryism – How the Only “ISM” Fair for Everyone Leads to Harmony, Prosperity and Good Karma for All! Drawing on Dr. Block’s extensive research and insights from his book The Privatization of Roads and Highways, Dr. Block makes a compelling case for privatizing road infrastructure. He argues that private ownership can enhance safety, reduce traffic fatalities, and improve efficiency through competition and innovation. Highlighting both ethical and economic advantages, Block explains how privatization could alleviate traffic congestion and significantly lower the staggering 40,000 annual road fatalities in the U.S., which he attributes to government mismanagement. He also addresses common concerns, such as the risks of monopolies, accessibility issues, and national defense implications, offering creative, market-driven solutions for these challenges. With wit and thoughtful analysis, Dr. Block dismantles the assumption that only government can handle critical infrastructure, demonstrating how privatized roads could deliver a safer and more efficient alternative.’

Full Transcript

Etienne de la Boetie2 Introduction:

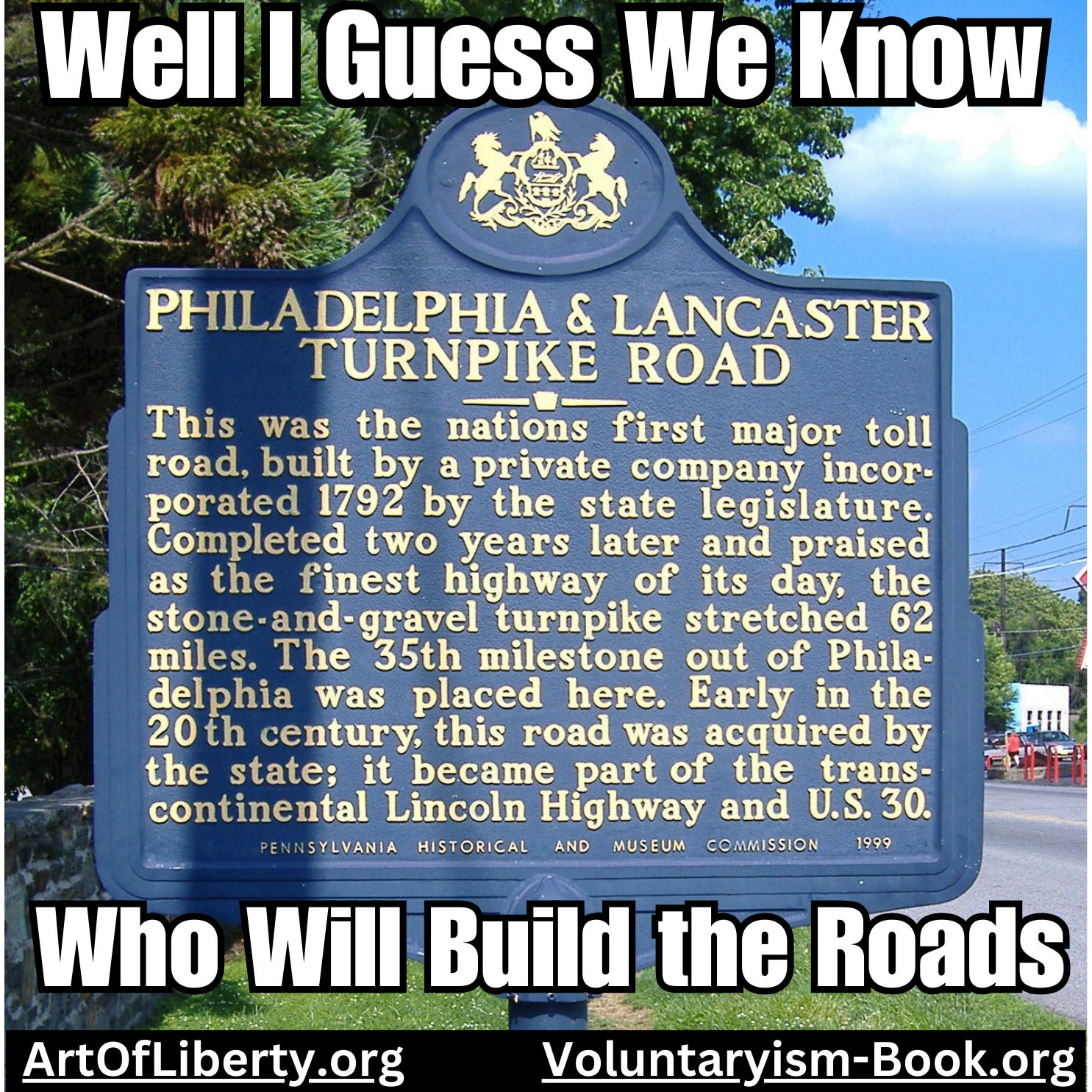

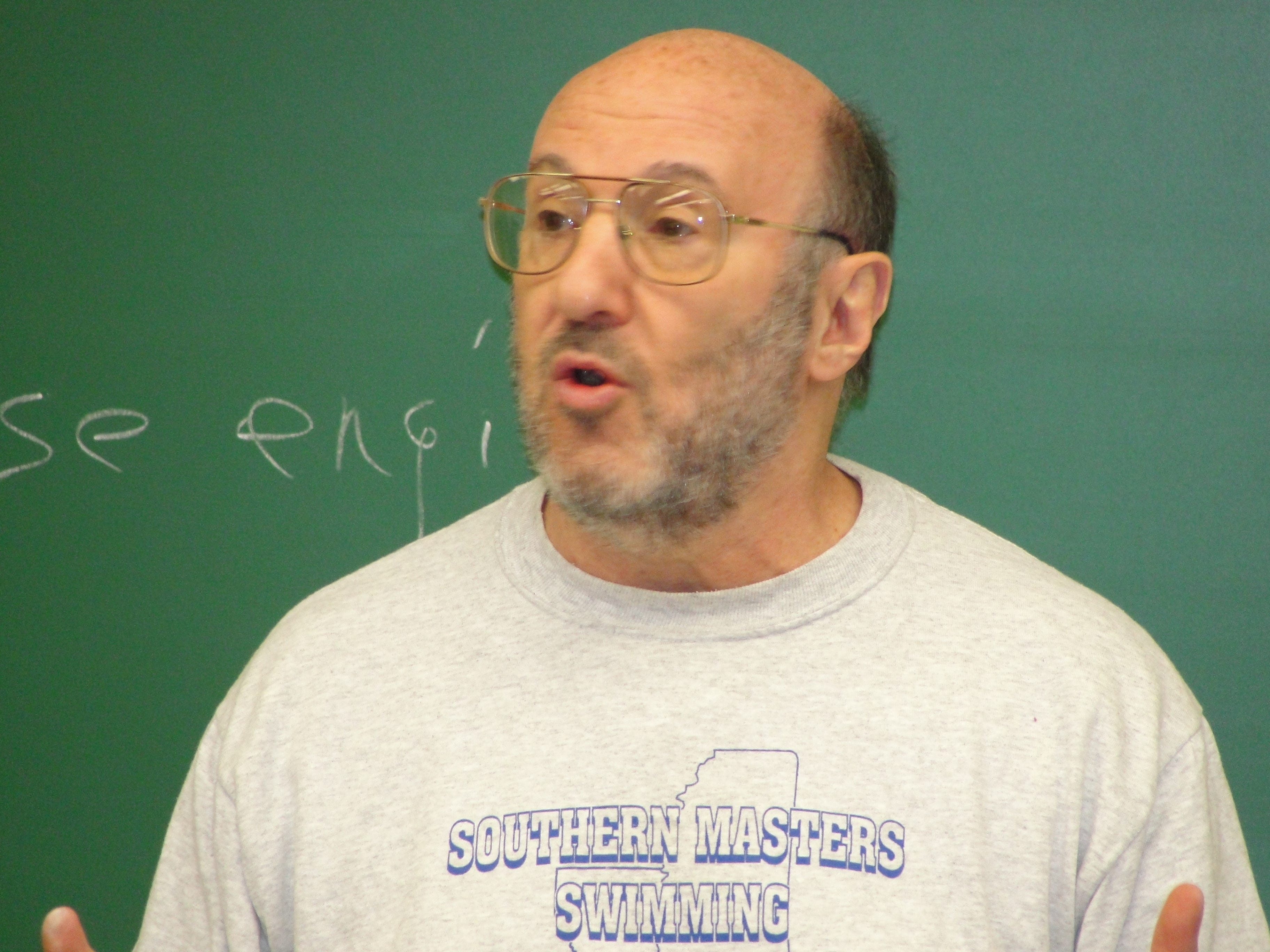

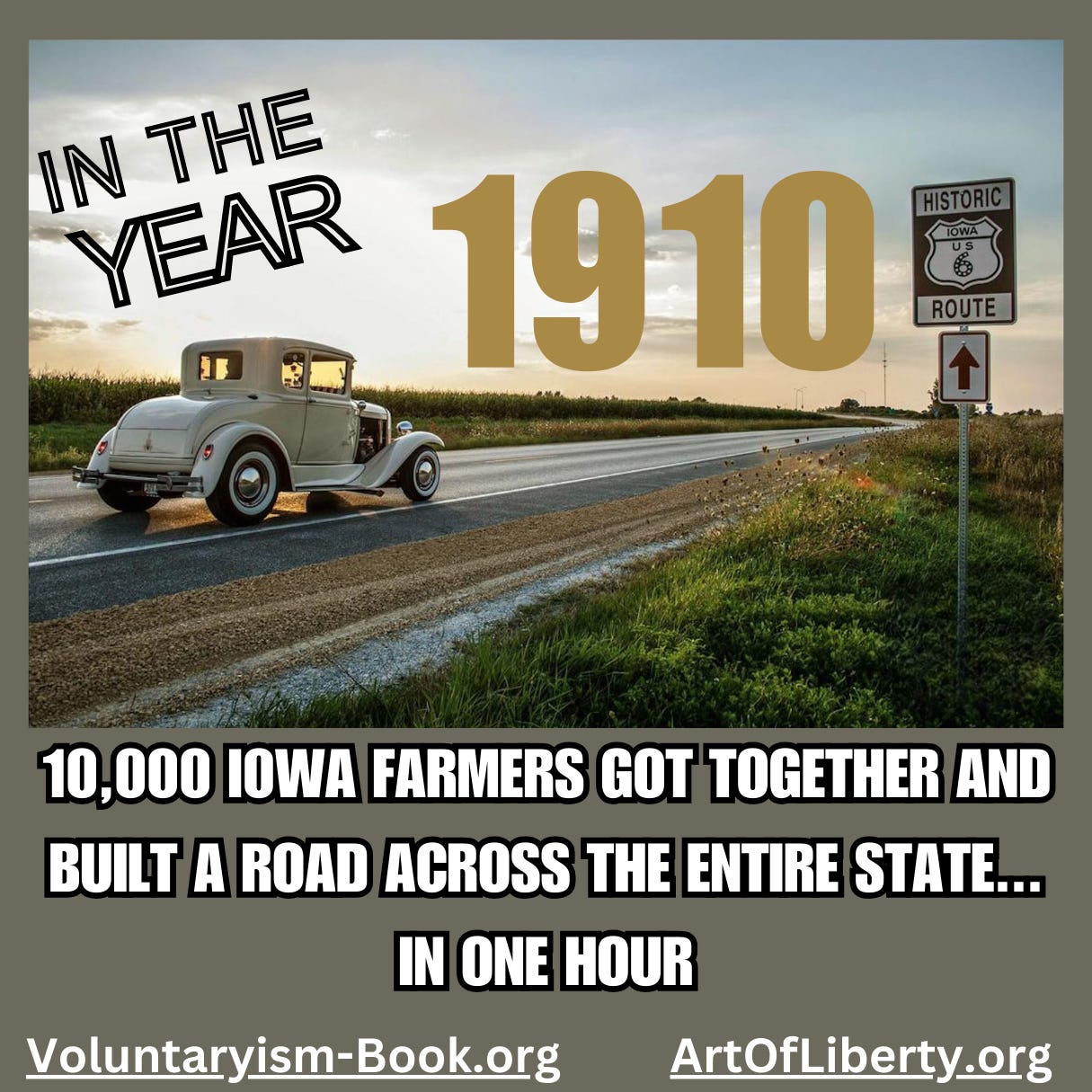

“But without government, who would build the roads?” This question has become something of a cliché in libertarian and voluntaryist circles, often used to highlight the unfortunate truth that many people rarely question the status quo or consider alternative ways society could function. The reality is that roads existed long before governments took charge of building and maintaining them—and, frankly, government management of roads has often been less than stellar. To help us explore this topic and answer the age-old question of who will build the roads and how, we are joined by a man who has, quite literally, written the book on the subject: Dr. Walter Block. Dr. Block is an esteemed economist, the former Harold E. Wirth Eminence Scholar Endowed Chair in Economics at the School of Business at Loyola University New Orleans, and a former senior fellow at the Ludwig von Mises Institute, a nonprofit think tank. With over two dozen books to his name, his most relevant work for today’s discussion is The Privatization of Roads and Highways: Human and Economic Factors. It is my pleasure to introduce Dr. Walter Block.

Walter Block: Thank you for the kind introduction, Etienne. However, I noticed you used the word former twice—one was accurate, and the other wasn’t. I’m not the former endowed chair at Loyola University; I’m actually the current one. But you were correct in stating that I’m the former senior fellow at the Mises Institute. I’m no longer associated with them—let’s just say we had a little disagreement over Israel.

That aside, I’m delighted to address your audience on the question of who would build the roads and how privatized roads would function. My overarching motto for privatization, whether it’s roads, highways, oceans, rivers, or even outer space, is this: If it moves, privatize it. If it doesn’t move, privatize it. Since everything either moves or doesn’t, the logical conclusion is that we privatize everything.

What’s the case for privatizing anything? There are two primary arguments. The first is efficiency. In a private system, if you do a good job, you can grow your business, expand your operations, and satisfy more customers. However, if you fail—if you consistently lose profits—you face the prospect of going bankrupt, forcing you to either improve or exit the market. This system of accountability ensures that inefficiency is weeded out over time. That’s why we generally have good-quality products in the private sector—pens, books, shirts, and countless other items. They’re not perfect, of course, because humans are inherently fallible and mistakes happen, but the private sector excels at delivering quality because of this built-in mechanism for improvement.

The second argument for privatization is rooted in ownership itself. Broadly, there are only three possibilities for ownership: privatization, government ownership, or non-ownership (what is often referred to as the tragedy of the commons). In the case of non-ownership, the lack of clear accountability leads to neglect and overuse. For instance, the reason we face problems like overfishing or the depletion of whale populations is because nobody truly owns the fish in the ocean. When something belongs to everyone, it effectively belongs to no one, and there’s little incentive to take proper care of it.

Non-ownership, or common ownership, presents significant problems. When everyone owns something, effectively no one does, which means no one takes proper care of it. This leads to issues like the tragedy of the commons, where resources—such as fish in the ocean or whales—are overexploited and depleted because no one has a vested interest in their sustainability.

Government ownership, on the other hand, is highly problematic from an ethical standpoint. Governments are inherently coercive institutions, and libertarians stand firmly against coercion. We advocate for voluntary interactions, not force, and the government embodies coercion in its very nature. That leaves private ownership as the only ethically legitimate option for managing resources and institutions.

It’s easy to see the case for privatizing certain things, like the post office or sanitation services. But what about highways, roads, and streets? This is where I’ll focus now.

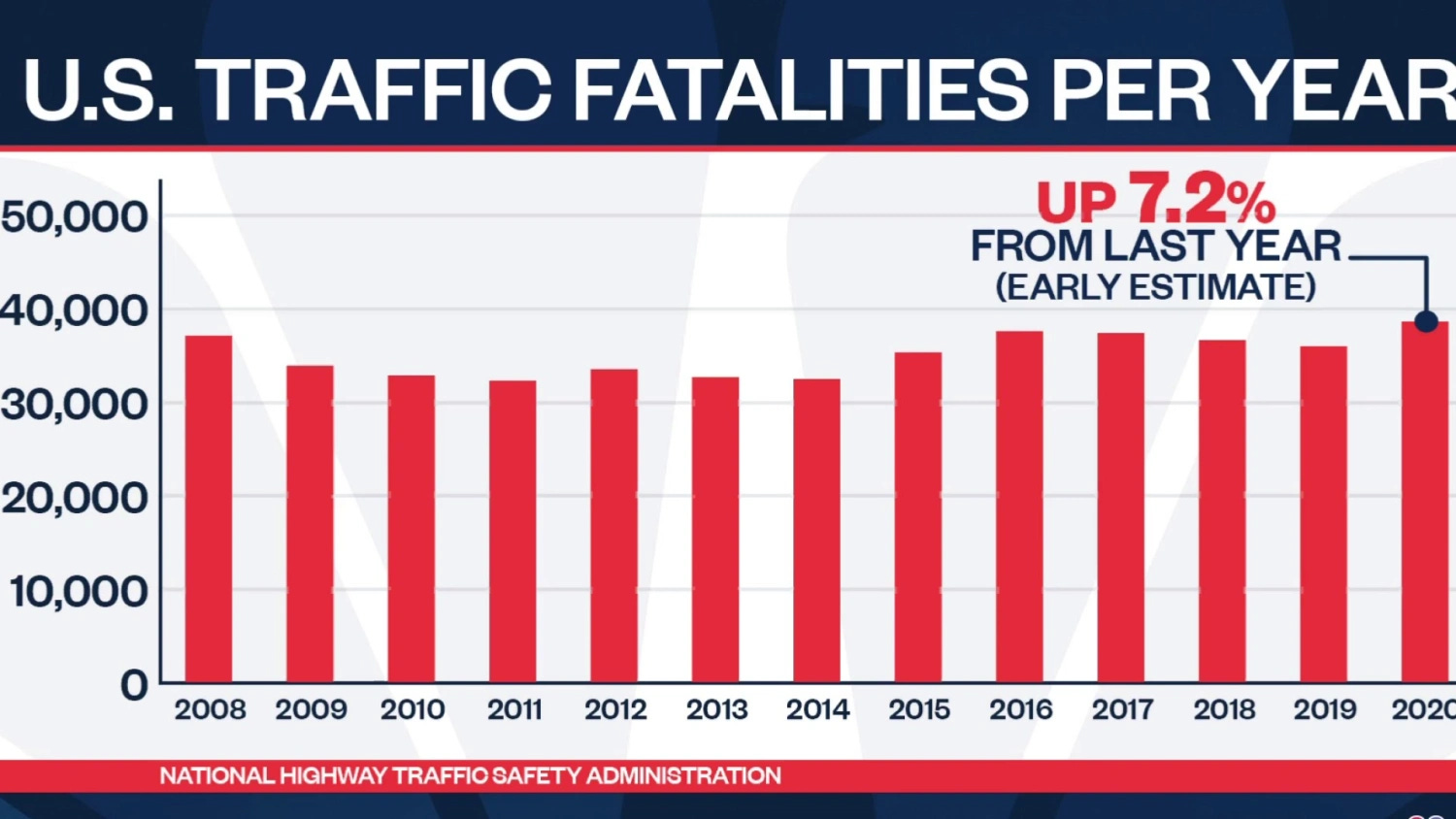

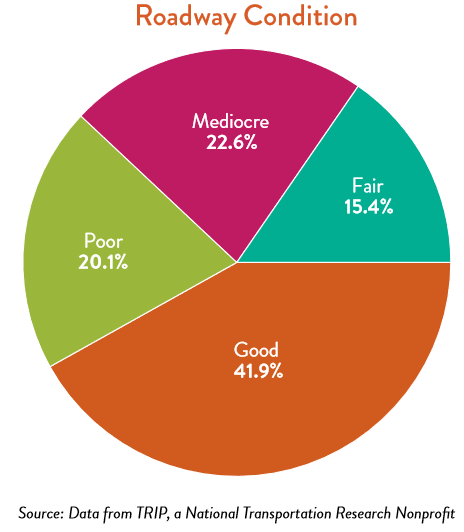

The main argument for privatizing roads and highways is safety. Currently, around 40,000 people die every year on U.S. roads. Forty thousand lives lost annually—this is a staggering figure. For context, consider that approximately 3,000 people died in the 9/11 attacks, and around 1,900 people died during Hurricane Katrina in New Orleans, where I currently live. These were tragic events, yet the annual death toll on U.S. roads dwarfs them.

To further contextualize, let’s compare this to current events. According to reports from the Gaza Health Ministry (operated by Hamas), over 40,000 people have died in Gaza, and the world rightly recognizes this as a humanitarian catastrophe. Indeed, whenever 40,000 lives are lost, it is undeniably horrific. Yet, in the U.S., this same number of people dies every single year on the roads, along with hundreds of thousands suffering serious injuries. This ongoing tragedy deserves far more attention and demands a better solution.

Hopefully, the tragic events in the Middle East will be limited to one year, and peace will eventually prevail. But if the future resembles the past, the U.S. will continue to see 40,000 deaths on its highways every single year—and that’s absolutely horrific.

You’ve likely heard the saying: there are only two things in life that are inevitable—death and taxes. Well, while I’ll begrudgingly accept that death is inevitable, I don’t agree that taxes are. And I certainly refuse to accept that 40,000 highway deaths every year are inevitable.

So why are so many people dying on the roads? The answer lies in monopoly. Our roads are government-run, and monopolies inherently lack competition. Competition is what drives improvements in quality, safety, and innovation. Think about it—we have excellent pens, scissors, shirts, and even paperclips, all because businesses compete to provide the best products. But with highways, there’s no competition.

Take I-10, for example, the highway that runs through New Orleans and stretches from Florida to California. If it were privately owned and poorly managed, the owner would face financial losses, leading to a hostile takeover or the need for new ownership. Competition would ensure that someone else, someone better equipped to manage the highway, would step in. But with government ownership, there’s no such mechanism. Mismanagement persists because there’s no accountability or incentive to improve.

To illustrate this, consider McDonald’s—a massive global company. Not long ago, an incident occurred where McDonald’s was responsible for one death and injuries to 45 people. Now, McDonald’s is an enormous corporation selling billions of burgers, so they survived the backlash. But if something like that happened repeatedly, if McDonald’s killed 40,000 people annually, the company would cease to exist. Customers would abandon them, and they’d be replaced by competitors offering better and safer alternatives. This is the power of competition—a power we’re missing entirely when it comes to roads.

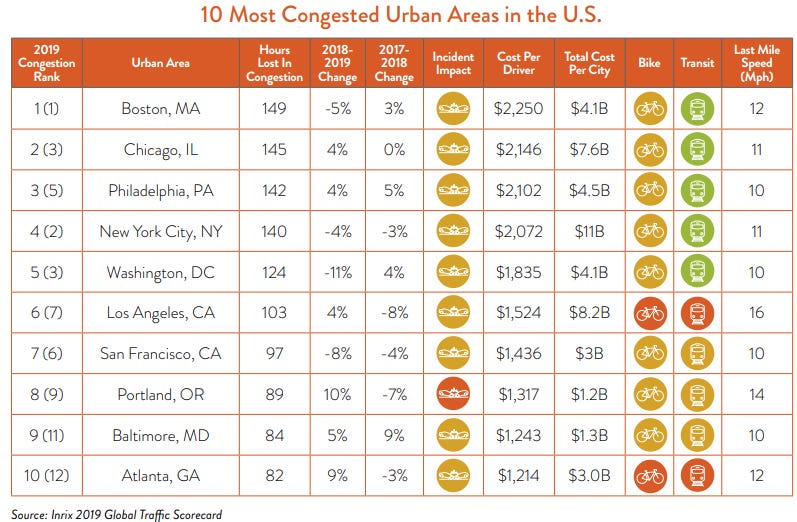

If McDonald’s failed us repeatedly, we’d simply go to Burger King, Wendy’s, or any other competitor. This highlights one key argument for privatization: competition leads to better outcomes. But my other major motivation for privatization is traffic congestion.

In many cities—New Orleans, where I now live, New York City, where I used to live, Seattle, where I visit often, and countless others, including cities in California—traffic congestion is a disaster. The average speed of traffic in these places is often slower than a bicycle, and sometimes even slower than a runner. A runner can manage about 12 miles per hour, while a walker might cover a mile in 20 minutes. Yet, drivers often find themselves stuck in bumper-to-bumper traffic, barely moving.

Take the Long Island Expressway, for example—infamously referred to as the “longest parking lot in the world.” Stretching around 100 miles, it frequently grinds to a standstill, leaving drivers just sitting there. This kind of gridlock is absurd and completely avoidable.

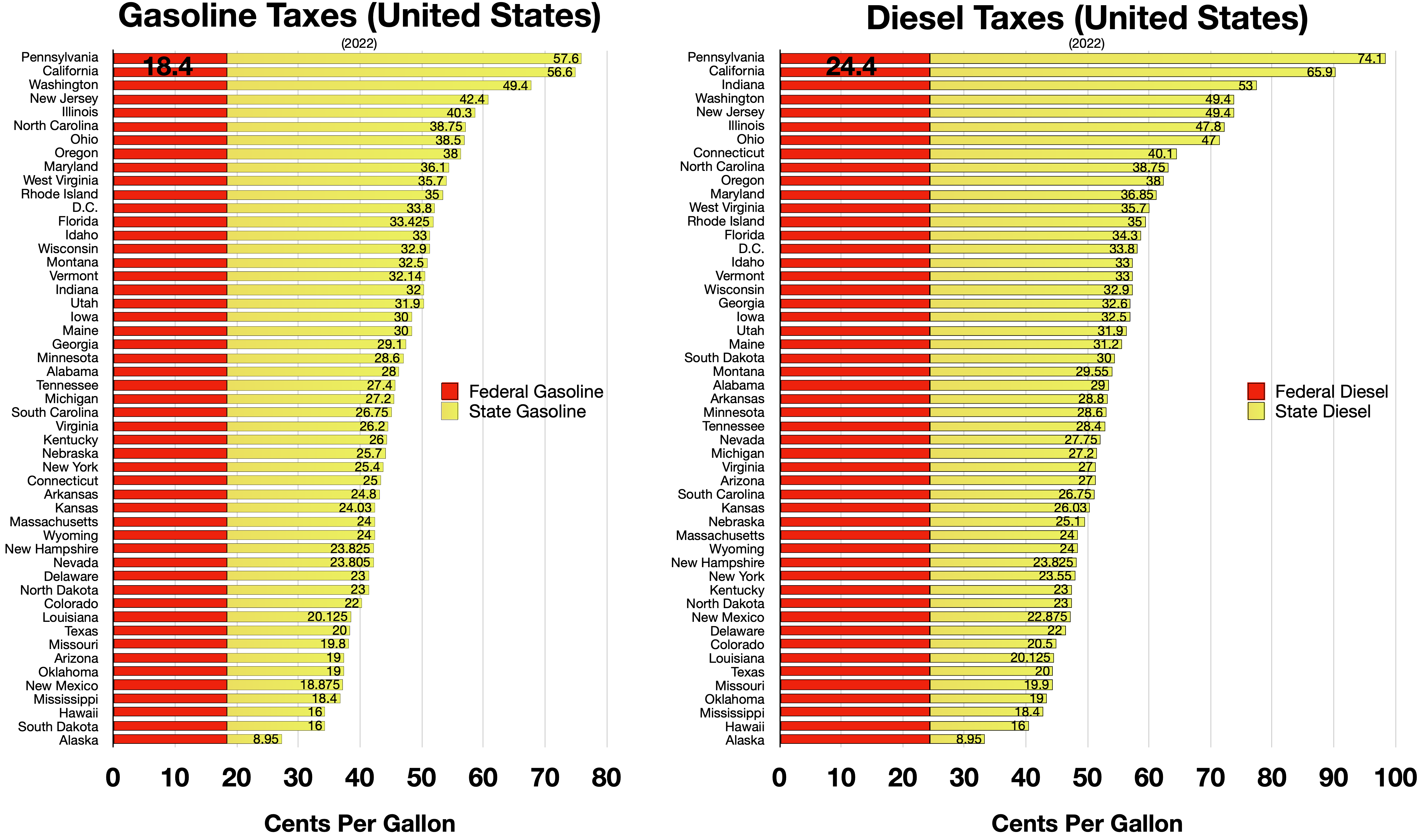

What’s the root cause of traffic congestion? Let’s break it down. Picture a basic supply-and-demand chart: on one axis, you have quantity, and on the other, price. The demand curve intersects with the supply curve to determine the price. Now, what’s the price you pay to use roads like the Long Island Expressway, I-10, I-5, or I-95? Zero. You don’t pay anything at the moment you use the road because you’ve already paid—through taxes, income taxes, or gasoline taxes.

This zero-price system means there’s no immediate cost to using the highway, so there’s no mechanism to regulate demand. Everyone piles onto the road at the same time, creating congestion. It’s a classic case of economic mismanagement.

What we’re dealing with here is basic supply and demand. When the amount of road space supplied falls short of the amount demanded, we end up with a shortage—and that’s all a traffic jam is: a shortage of available road capacity. It’s a simple concept rooted in economics, yet it’s something we constantly experience on government-run roads.

Apologies for the technical hiccups—I’m not great with whiteboards, but I think I’ve sorted that out now. Let’s move on.

My two main motivations for privatizing roads are straightforward. First, the shocking loss of life: 40,000 people die on U.S. highways every year. That’s a staggering number, and chances are that everyone listening to this either knows someone—or knows someone who knows someone—who has died or been seriously injured on the roads. It’s a national tragedy, yet it’s rarely discussed in the media. Think about it—when Hurricane Katrina hit or the 9/11 attacks occurred, the news was dominated by those events, as it should have been. But 40,000 highway deaths occur every single year, and it’s largely ignored.

The second major issue is traffic congestion, which I’ve already touched on. But now let’s ask: how could private ownership of roads make things better?

For one, private roads would likely handle speed limits differently. On government roads today, there are arbitrary speed regulations. For example, highways often have a minimum speed limit of 40 mph and a maximum of 70 mph. If you can’t go at least 40 mph, you’re not allowed on the highway, and if you exceed 70, you’re technically breaking the law. However, enforcement is inconsistent. Drivers routinely go 75, 80, or even higher without receiving tickets—unless they’re unlucky or the police officer is in a bad mood that day.

Now consider the left lane, which is meant for faster traffic. If you’re driving 70 mph in the left lane, you’ll often find cars overtaking you in the middle lane. At night, drivers will flash their high beams at you, honk, or otherwise signal that they think you’re a “clod” or a “moron” for blocking the faster lane. Although there are occasional signs advising slower cars to stay in the right lane, enforcement is virtually nonexistent. You could drive 65 mph in the left lane, frustrating everyone else, and you’d almost never get a ticket. This lack of clear rules and enforcement creates chaos and inefficiency on the roads.

Private ownership could address this. A private road owner has an incentive to set rules that maximize safety, efficiency, and customer satisfaction. If they fail to manage their roads effectively, they lose business or face competition. This kind of accountability is absent in government-run road systems, and the consequences are both deadly and frustrating for drivers.

Okay, let me pull up the screen again and ask you all a question. Imagine we have three lanes: the left lane, the middle lane, and the right lane. Now, suppose I own a road and implement this rule: everyone in the left lane must drive 60 miles per hour, everyone in the middle lane must drive 70, and everyone in the right lane must drive 85. No deviations—no 65, no 75, no odd speeds. The question is: would this save lives?

The honest answer is, we don’t know. Maybe this system would save lives. Or maybe the limits should be lower—say 55, 70, and 85. But again, we just don’t know. And that’s the issue.

In other industries, we can experiment and learn what works best. For example, people make shirts, scissors, pens, and even rabbits in all sorts of ways. (Yes, rabbits—don’t ask me why I mentioned rabbits, but stick with me here.) Some methods are better than others, and through trial and error, we learn which approaches are most effective. But when it comes to roads, we don’t have the freedom to experiment because Washington, D.C., mandates the rules. The government says the minimum is 40 mph, the maximum is 70 mph—and that’s it. There’s no room for innovation.

Let’s try another idea. Here’s a new whiteboard. Again, we have three lanes: left, middle, and right. Suppose we created a rule where, if someone passes you on the middle lane while you’re driving in the left lane, you automatically get a ticket. Would that work?

Honestly, I don’t know. Nobody knows. My theory is that the more lane-switching there is, the more accidents and deaths occur. So, if we had a system where everyone drove a specific speed in a specific lane, it might reduce lane switching and, in turn, reduce fatalities.

But again, I don’t claim to be a road safety expert. What I do know is that under private ownership, road owners would have the incentive to experiment, innovate, and figure out what systems work best to maximize safety and efficiency. That’s something we’re simply not getting with government-run roads.

What do I know about roads? Not much, I admit. There are people who are road experts—engineers who go to school and study these things. Unfortunately, in those schools, they rarely, if ever, teach about private roads or alternative ways of managing roadways. But here’s something I posit, something I hypothesize: lane changing is dangerous. Obviously, some lane changing is unavoidable, but if we could minimize it, maybe we’d save lives. I don’t know for sure—but the problem is that no one knows. And the current system, with government-run roads, isn’t set up to allow us to find out.

Let me try another example. Imagine a two-lane highway, with both lanes going in the same direction. Here’s one truck in the right lane, and here’s another truck right behind it. (Apologies for my drawing—no, I’m not drunk, I’m just not great at drawing rectangles on a screen.) Now, when I see one truck following another like this, I know what’s going to happen: the rear truck is going to try to pass the first truck. And it’s going to take forever—maybe 15 miles—for this truck to creep past the other. It’s like watching a slow-motion race.

What do I do in this situation? Well, I hate to admit it—and I hope no police officers are listening—but I’ll step on the gas and try to pass both trucks before they block me in. It’s risky, I know. I shouldn’t be speeding, and I definitely shouldn’t be speeding more just to avoid trucks. But what else can I do?

Maybe we need a system where the slower truck gets a ticket for not letting the faster truck pass. I’m not sure of the exact solution, but I do know that this kind of problem happens all the time, and I’ve never seen a cop pull over a truck for blocking a faster vehicle. These are just some of the issues that private roads might address—and possibly solve—in innovative ways.

Here’s another idea. If I owned a highway—let’s call it the Walter Highway—one thing I’d do to reduce accidents is install highly visible warnings in dangerous areas. For example, whenever there’s a part of the road where many deaths have occurred, I’d put up a large marker—a Christian cross, a Star of David, an Islamic crescent, or another symbol—depending on the individual involved. These markers wouldn’t be small. They’d be 50 or even 100 feet tall to make them impossible to ignore. The idea is to scare people into driving more carefully by visually reinforcing the dangers of that section of road. Maybe the road tilts, maybe it’s poorly lit, or maybe it has sharp curves—but whatever the reason, these markers would help alert drivers to areas where caution is needed.

These are just a few of the ideas I explore in my book. The first half focuses on innovative ways to improve safety on roads, while the second half addresses common objections to privatization. I’ll get to those objections shortly, but for now, the point is clear: with private ownership, we could experiment with different methods to make roads safer. Government-run roads simply don’t allow for that level of innovation.

Okay, it might not sound nice, but my focus here is on reducing deaths. I’m speculating on how private ownership and competition could help accomplish that. As I mentioned earlier, about half of my book is dedicated to explaining why privatizing roads could save lives and reduce congestion. I’ve given you a small taste of those ideas so far. The second half—or maybe it’s closer to two-thirds, I haven’t checked recently—addresses objections to road privatization. So let me go over some of the common objections people raise.

But before that, a quick note on drunk driving. Some might argue that reducing highway deaths could also mean taking a tougher stance on drunk or drugged driving. For instance, instead of just handing out fines, maybe we should be confiscating cars or putting offenders in jail. Some libertarians, however, might push back and say, “Just being drunk isn’t a crime. Are you suggesting we bring back Prohibition?”

Of course not. But here’s the thing—if roads were privately owned, the owner could set the rules. If it’s my road, I could say, “Look, if you’re drunk or drugged, you’re not welcome here. If you’re caught, I’ll kick you off my road or even ban you entirely.” That wouldn’t violate anyone’s rights. Just like in my home—if I say you have to wear a propeller beanie to come into my living room and you refuse, you’re violating my rights. Private ownership allows for clear rules and enforcement, which could be another tool for reducing deaths.

Now, let’s address some objections to privatizing roads. One common argument is that road deaths aren’t the government’s fault—they’re caused by drunk driving, speeding, vehicle malfunctions, texting, driver error, and so on. There’s some merit to that claim. For example, the economist Sam Peltzman, whose work on the FDA I greatly admire (he’s a brilliant free-market thinker), has identified about 25 different causes of road deaths. However, in his analysis, he never once mentions government ownership of roads or considers privatization as a factor.

But here’s the problem with that objection: while it’s true that these are direct causes of road deaths, the underlying system matters too. Government-owned roads create a lack of accountability and innovation. Private owners, on the other hand, would have strong incentives to implement systems that minimize these risks—whether that’s better technology, stricter rules, or more efficient road designs. Ignoring the ownership model in this discussion is a significant oversight.

Sam Peltzman never mentions government ownership of roads as a factor in road deaths. And then there’s the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA), which has compiled a list of 125 different causes of highway deaths. That’s right—125 causes. They’ve gone to incredible lengths to be meticulous with their analysis.

For example, one cause is whether there’s a hood ornament on the front of the car, which can increase the likelihood of injury. Another is the distance between the road and the nearest hospital—the idea being that the closer the hospital is, the fewer deaths occur. That makes sense. They also consider whether the hospital has a helicopter. A helicopter allows for much faster transportation of seriously injured people compared to an ambulance on the road, which could save more lives.

It’s an impressive level of detail, but here’s the striking thing: in all 125 causes listed by the NHTSA, government ownership is never mentioned. Not once. I mean, what’s with that? How can you analyze road deaths so thoroughly and ignore the foundational issue of who owns and manages the roads?

This brings me to another objection I often hear: the difference between proximate and ultimate causes. Let me illustrate. Suppose I were to shoot Etienne—don’t worry, I’m not actually going to shoot you, Eteinne. If the bullet hits him and kills him, the police would come and arrest me for murder. Now, I could argue, “Hey, it wasn’t me—it was the bullet that killed him!” But nobody would buy that for a second. I’d be held responsible as the ultimate cause.

The same logic applies to road deaths. Sure, the proximate causes might be speeding, driver error, texting, or one of the other 125 factors listed by the NHTSA. But the ultimate cause is the system itself—the government ownership and mismanagement of roads. Without competition or accountability, there’s no incentive to innovate or create safer systems. So while proximate causes are important, ignoring the ultimate cause—government monopoly—is a major oversight.

But the ultimate cause of traffic fatalities is the government, just as the ultimate cause of a murder would be me, not the bullet. The government is responsible for the system that leads to these 40,000 deaths annually, not the 125 proximate causes.

Now, another objection people raise is about the number of deaths that would occur if roads were privatized. In my book, I estimate that if private enterprises owned and managed the roads, there might still be around 10,000 deaths annually. Let’s be clear: private enterprise isn’t perfect. There would still be some fatalities, even in a privatized system. But the goal isn’t perfection; the goal is to minimize deaths.

Zero deaths, while ideal, isn’t realistic. To achieve zero highway fatalities, you’d have to impose a speed limit of about 15 miles per hour. And sure, at 15 miles per hour, it’s unlikely anyone would die in a crash. But this would create another massive problem: trucks couldn’t deliver goods efficiently, supply chains would break down, and people might literally starve. So, from a macro perspective, zero deaths might not even be the optimal goal.

This brings us back to the distinction between proximate and ultimate causes. If roads were privatized and 10,000 deaths still occurred, would we blame capitalism for those deaths? No. Traveling at normal highway speeds—50, 70, 90 miles per hour—comes with inherent risks. But under private ownership, the system would likely innovate to reduce risks and cut fatalities dramatically compared to the current government-run system.

Now, critics might object, saying: “If 10,000 deaths would still occur under privatization, and there are currently 40,000 deaths, then the government isn’t responsible for all 40,000 deaths—it’s only responsible for the excess 30,000 deaths.” That’s a fair point, but it doesn’t absolve the government of its failure. Even if we accept this argument, the fact remains: private roads could reduce deaths by 75%, which is a staggering improvement. The government’s role as the ultimate cause of these excess deaths is undeniable.

You get the idea. One objection to my theory that the government is responsible for 40,000 deaths annually is that I concede 10,000 people would still die even if the roads were privatized. The objection goes: “Well, then the government is only responsible for 30,000 deaths.” I reject this argument outright.

Let me illustrate with an analogy. Hitler is accused of killing six million people over four years. Let’s stipulate that’s true. In those four years, it’s reasonable to estimate that 100,000 people would have died of natural causes. Does that mean Hitler is responsible for only 5.9 million deaths instead of six million? Of course not. He’s responsible for all six million deaths. Similarly, the government is responsible for all 40,000 traffic deaths because it controls the roads. Proximate causes like speeding or driver error don’t absolve the government of its role as the ultimate cause.

Now, let’s move on to another objection: the idea that if private enterprise owned the roads, traffic would come to a halt—not bumper-to-bumper gridlock, but because drivers would have to stop at toll booths every time they passed a collection device. This objection is outdated and highly problematic.

When I first started writing and researching this topic back in the 1980s, I was studying groceries. Don’t ask why—well, actually, do ask, and I’ll tell you. At the time, supermarkets were just starting to implement barcode scanning technology. Here’s where my rabbit analogy comes in. Let’s say I’m buying a rabbit. The rabbit has a barcode on the bottom, and when you pass it over a scanner, it goes beep, registering the price and identifying it as “one rabbit.” This allows the store to not only ring up your purchase but also track inventory so they can restock as needed. Back then, I thought, “Why couldn’t we do something similar for roads?”

Today, this is commonplace. Every supermarket has this kind of scanning system. My idea was to put a similar mechanism on roads. For example, we could install a tag or chip on the underbody of every car. The road itself would have sensors to automatically register each car as it passed. Instead of stopping to pay a toll, the system would track your usage, and you’d receive a bill at the end of the month or year. Alternatively, you could prepay into an account, and the toll system would deduct the appropriate amount as you drove.

This technology already exists in many places today, with systems like EZ Pass or other electronic tolling methods. So the objection that privatized roads would require constant stops to pay tolls is simply outdated and invalid. Modern technology solves this issue efficiently.

And so, I would reject that objection outright. Let’s move on to another common objection: privacy.

Some people worry that if roads were privately owned, the owners might track your movements. For example, they could know where you’re driving, when you’re driving, or even if you’re visiting your proctologist—something no one really wants anyone to know about. So, what about privacy?

On my private road, I would assure customers that the only thing I care about is how far they traveled. I wouldn’t care where they were going, why they were going, or any other personal details. The only data I’d collect would be strictly about road usage, not personal destinations. Privacy concerns are valid, but they can be easily addressed with clear policies and practices.

Now, let’s consider another objection. Imagine this scenario: Etienne owns the road leading to my house, and Etienne decides to charge me a million dollars every time I want to leave or return home. Essentially, he traps me in my house unless I pay his exorbitant fee. This kind of behavior would be a disaster and a legitimate concern for those skeptical of private roads.

So, what’s the answer to this objection? The answer is simple: Howard would never do this. If he did, he’d be a maniac—and a maniac doesn’t stay in business for long. Howard’s goal as a road owner would be to maximize profits, which means encouraging people to use his road, not scaring them away. He would want homes, businesses, shopping malls, factories, or even high-rise residential buildings along his road. An empty road generates no revenue.

To attract people to build homes or businesses along his road, Howard would need to contractually obligate himself to reasonable terms. Before I built my house on his road, I’d want to know: “Howard, what’s your deal? What’s your policy? Can you charge me outrageous amounts of money at will?” If Etienne’s terms were unreasonable, I wouldn’t buy a house there, and no one else would either.

This is the beauty of market forces. Howard has every incentive to establish fair and transparent agreements to encourage people to use his road. Otherwise, he’d go broke. Roads, like any other private enterprise, rely on creating value for their customers, not exploiting them.

So, what would Etienne need to do to attract customers to his road in the first place? He’d have to establish contractual obligations to ensure fair treatment. For example, he might say, “I won’t charge any occupant of a house on this road more than anyone else,” or “For the next 10 years, I’ll charge this fixed amount.” These agreements would preclude him from exploiting homeowners. That’s the answer to this objection: market forces would compel Etienne to offer fair terms to attract customers in the first place.

Now, let’s move on to another objection—this one’s a technical economic argument: the claim that roads are a “natural monopoly.” The argument goes that roads, unlike products like rabbits, pens, or scissors, naturally tend toward monopoly because only one company can realistically own all the roads in a given area.

But here’s the thing: we already have other “long, thin” infrastructures that are privately owned, such as railroads. If roads inherently had to be monopolized by a single owner, how do we explain the existence of multiple competing railroads? Railroads are similar to roads in many ways—both involve long, thin corridors of infrastructure—but we’ve seen examples of different companies successfully owning and operating different railroads.

Yes, in many cases, railroads have been government-subsidized or outright government-owned, but that wasn’t always the case. In fact, in New York City, the subway system originally had competing private ownership. For example, the IRT (Interborough Rapid Transit) and the BMT (Brooklyn-Manhattan Transit) were privately owned, while only the IND (Independent Subway System) was government-run.

What happened? The private companies were charging riders a nickel per ride and eventually wanted to raise the fare to a dime. The city government stepped in and said, “No, this is unacceptable. You can’t raise fares.” This interference undermined the financial sustainability of the private subway systems, eventually leading to their takeover by the government.

The key takeaway here is that there’s nothing inherent about roads—or similar infrastructure—that makes them a natural monopoly. With fair rules and competition, private ownership of roads is entirely feasible, just as it was for railroads and subways in the past.

That’s doubling! So, the government took over the private subways, nationalized them, and guess what they did? They charged a dime anyway. Go figure. Back when this happened, I had a full head of hair—look at me now! I’ve pulled it all out over the absurdity of this nationalization.

Now, let’s look at another example in New York City: the FDR Drive, the highway running along the east side of Manhattan. In some sections, it’s a double-decker road, with one level stacked on top of the other. That’s an example of how you could have competition—by building one road over another.

Let me pull up the drawing board again to explain this. Here we go. Imagine you want to build a road from Boston to Seattle, roughly 3,000 miles. The ideal route would be a straight line—as the crow flies—because deviations from a straight path increase costs and make the trip longer.

But you don’t have to build your road perfectly straight to compete. For example, one road might veer slightly north, another might veer slightly south, and another might stay closer to the middle. Let’s say the vertical distance between these competing roads is only 10 to 15 miles. That’s not a big deal—it’s still competition, even though the roads aren’t exactly parallel or straight. Everyone with me? I hope my drawings make sense, but the point is this: you don’t need exact replicas of roads to have competition. Roads can vary slightly in direction and still provide viable alternatives for drivers.

Now, as I mentioned, you could also have one road directly above another or even tunnels below. However, that raises an issue known as the ad coelum doctrine. What’s ad coelum? It’s a legal principle that states if you own a piece of land, you own a cone extending downward to the core of the Earth and upward into the heavens. So, under the ad coelum doctrine, if I own a road, you couldn’t build another road above or below mine because I’d own everything vertically along my land’s boundaries.

But we libertarians reject the ad coelum doctrine. Why? Because libertarians believe that ownership is based on homesteading. In other words, you can only own what you’ve actively used or transformed. Nobody has homesteaded 25 miles beneath the Earth’s surface or several miles into the sky, so you can’t claim ownership of those areas just because you own a piece of land on the surface.

This rejection of the ad coelum doctrine allows for things like slant drilling in oil production. For example, I could drill on my property, but if I drilled diagonally under your property, that could still be considered legitimate under certain agreements or frameworks. Similarly, when it comes to roads, rejecting ad coelum means we could have tunnels beneath existing roads or highways stacked above them, enabling even more competition in road ownership and usage.

As long as I don’t cave in your buildings, there’s nothing wrong with building a road above or below existing structures. So, the idea of stacking roads or creating tunnels to increase competition is perfectly feasible.

Now, while I’ve got this beautiful diagram up, let me address another common objection: Do we need eminent domain to build roads?

Take a road from Boston to Seattle, a journey of about 3,000 miles. How many people own land along the way? I don’t know—maybe 1,000, 10,000, or even 100,000 people might own parcels of land on that route. This raises the classic “holdout problem.”

Here’s how it works: Let’s say there’s a guy who owns a square mile of land smack dab in the middle of the planned route. He says, “Sure, you can build a road through my property—but it’ll cost you a trillion dollars.” Or worse, he might say, “Nope, I’m not selling. Grandma gave me this land, and it’s staying just the way it is. I don’t want a highway cutting through my property. The hell with you!”

This is where my favorite cartoon character, Cartman from South Park, comes in. Everyone knows what Cartman stands for: “Screw you guys, screw you guys, screw you guys.” Now, imagine that Cartman owns a critical chunk of land right in the middle of every feasible route between Boston and Seattle.

Here’s the map: Highway 1, Highway 2, Highway 3, and Highway 4—these are all potential routes we could use to build the road. But Cartman owns key pieces of land on every single one of these paths. And, true to form, Cartman says, “Screw you guys, I’m not allowing you to build a road!”

This is a serious objection. Without eminent domain, how can we deal with holdouts like Cartman? How do we build roads when someone is determined to block every possible route? Critics argue that private roads couldn’t exist without the power of eminent domain because holdouts would make large infrastructure projects impossible.

So, don’t we need eminent domain? Doesn’t the government need to step in and say, “Look, Cartman, we’re going to take your land. We’ll give you what we think is fair market value, and then we’re putting a road right through your property. If you don’t like it—too bad. Go lump it.” That’s essentially what eminent domain is. In Canada, I believe they call it expropriation.

But here’s the thing—there’s an alternative. Instead of taking Cartman’s land outright, you could build a tunnel under his property or a bridge over it. And since libertarians reject the ad coelum doctrine (the idea that land ownership extends infinitely up into the sky and down into the Earth), Cartman couldn’t claim, “I own the air above and the ground below my property, so you can’t build there.” He doesn’t have that right under our framework.

Now, this brings me to a fascinating discussion I had with my son years ago. He’s 46 now, but when he was about 15, we spent over a year debating this very question: “What could Cartman do to stop us from building over or under his land?” We came up with a clever idea: Cartman could theoretically drive stakes—literal sticks—deep into the ground below his property and high into the air above it. If he did that, those barriers could block both a tunnel and a bridge.

And that brings me to something I call football theory. Let me explain. Imagine a football field. At either end, you’ve got the end zones. Team A (that’s us) wants to move the ball toward Team B’s goal line. Now, at the start of the field, near point one, it’s much easier to move the ball. Why? Because you’ve got the entire field to work with. You can throw a long pass, run the ball, or try all sorts of creative plays.

But as you get closer to the goal line, the situation changes. The space becomes much tighter, and you lose the ability to maneuver. The defense can focus all their energy on stopping you because there’s less room for you to work with. It’s much harder to score when you’re right at the goal line.

The same principle applies to dealing with Cartman. At the beginning of a road project, when there’s lots of flexibility in choosing the route, it’s like being at point one on the football field—you have plenty of options. You can move the road slightly north or south, or adjust the route entirely. But as you narrow down the route and approach Cartman’s property, the options become fewer and fewer, just like approaching the goal line. That’s when the holdout problem becomes more difficult to solve.

So, let’s think about this football analogy again. All Cartman has to work with is the “end zone.” In this case, the road is like a football field that’s 150 feet wide—three lanes at 10 feet each (30 feet), plus a median of 40 feet. That’s 100 feet total for the lanes and median, plus an additional buffer of 50 feet. So, the offense only needs to move a “football” 150 feet wide.

Now, how much does Cartman have to defend? He has to defend 15 miles! Imagine that—Cartman has to maintain control over every inch of 15 miles to stop us. That’s the whole point: Cartman doesn’t have a chance.

Let me finish the story about my son. When we worked on this question together, I eventually wrote it up as a chapter in my book. But the big question was: Should my son be listed as a co-author? He was only 16 at the time, but we had spent over a year discussing this—football analogies, the ad coelum doctrine, and all the rest of it. Even though I wrote the actual chapter, the ideas came from both of us, so I decided to make him my co-author.

My son, being humble, said, “No one will believe I contributed. I’m just a kid.” But I told him, “I don’t care what people believe. I care about the truth. And the truth is, you’re my co-author.”

Now, here’s where the story gets interesting. Gordon Tullock, a famous economist who almost won a Nobel Prize, wrote a blistering critique of the Block and Block thesis. He didn’t hold back. He essentially said we were crazy, out to lunch, and completely unhinged (though I don’t think he actually used the word unhinged).

In response, I wrote a rebuttal. By that time, however, my son had lost interest in the debate—he became a “nerd,” as he put it, and moved on to other pursuits.

Let me summarize everything because I’m running out of time. The primary reason for privatizing roads is to save lives. Every year, 40,000 people die on U.S. roads. Privatizing roads would create accountability and innovation, which would drastically reduce that number.

Let me leave you with a quote from one of my favorite economists, Thomas Sowell:

“It is hard to imagine a more stupid or more dangerous way of making decisions than by putting those decisions in the hands of people who pay no price for being wrong.”

And that’s exactly what we have with the NHTSA—the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration. They preside over a system that kills 40,000 people every year. Now, I’m not saying they’re murderers or that we should punish them with the death penalty. But they are responsible for maintaining the government monopoly on roads, and they pay no price for being wrong. That is a deeply problematic situation.

There’s so much more I could say on this topic—there’s a lot more in the book. I wish I could be at the conference to answer your questions and dive deeper into these ideas. But for now, I’ll stop here.

Thank you.

So that was amazing. And so Dr.

Thanks for the question. In a voluntarist world, or a stateless society, who would protect the environment? The answer is simple: private courts and private defense agencies would protect the environment by defending property rights.

Let me give you an example. Suppose I’m your neighbor, and I take my garbage—eggshells, orange peels, coffee grounds, chicken bones, empty Coke cans—and I dump it all on your front lawn. If you’re a nice guy, maybe you’d first approach my wife and say, “Hey, Walter went berserk—look what he did!” And let’s say there’s no doubt that I did it. Maybe you have video evidence, or my fingerprints are all over the Coke cans.

Now, if you tried that approach and it didn’t work—or if you’re not feeling so nice—you’d call the cops. You’d say, “This is trespass. Walter dumped garbage on my property. Get him to stop, fine him, or throw him in jail.”

But let’s say instead of dumping my garbage physically on your lawn, I burn it. I incinerate the eggshells, coffee grounds, and chicken bones, and instead of sending over “macro garbage,” I send over micro garbage in the form of dust particles, smoke, and pollution that lands on your lawn—or worse, enters your lungs. Is there any real difference? No, it’s still a violation of your property rights.

Murray Rothbard addressed this beautifully in his essay on air pollution (I think it was from 1980 or 1982). He argued that air pollution isn’t a market failure—it’s a form of trespass. Just as if I physically walked onto your lawn and refused to leave, sending harmful particles onto your property or into your lungs is also trespass.

In a stateless society, this would be handled just like any other property rights violation. If I dumped garbage on your lawn or polluted your air, you’d go to your private defense agency or court and say, “Walter Block is trespassing against my property. Get him to stop and hold him accountable.” The defense agency would act on your behalf to defend your property rights and resolve the dispute.

So, who would protect against pollution in a voluntarist world? The same people who would protect against trespass or theft: private defense agencies and private courts. These institutions would enforce property rights, and by doing so, they’d protect the environment as an extension of protecting individuals and their property.

Excellent.

Ah, immigration in a voluntarist society—a topic that divides libertarians more than almost any other! It’s a contentious issue, with libertarian thinkers taking very different stances. For example, Murray Rothbard initially supported open borders but later changed his position to oppose them. Jacob Hornberger strongly favors open borders, while Hans-Hermann Hoppe supports what we might call “limited borders,” though not fully closed borders. It’s a complex debate, but I believe I have a solution that’s rooted in libertarian principles.

Let’s explore this with an example. Imagine someone from Mars—an alien—comes to Earth and lands in the middle of Alaska or the Rocky Mountains in Wyoming. This alien finds a patch of untouched, virgin land that’s never been homesteaded by anyone before. He starts homesteading it by planting crops, raising livestock, and putting the land to productive use. Along comes an agent from ICE (the Immigration and Customs Enforcement agency) who says, “Hey, you can’t do this! This is U.S. soil! Where did you come from?”

The Martian responds, “I came from Mars, but I haven’t violated anyone’s rights. I’m simply homesteading this unused land.” Now, the critical question is: under libertarian law, what rule has this Martian broken? The answer is: none. He hasn’t violated anyone’s property rights, and under libertarian principles, specifically those of John Locke, Murray Rothbard, and Hans-Hermann Hoppe, the first person to homestead unowned land becomes its legitimate owner.

In this scenario, the Martian is the rightful owner of the property he homesteaded. There’s no libertarian justification for ICE or anyone else to evict him, because he hasn’t violated anyone’s rights. This illustrates that the concept of “borders” is irrelevant to unowned land in a voluntarist society. Borders only exist insofar as they mark the boundaries of privately owned property.

This example highlights a core libertarian principle: property rights are rooted in homesteading and voluntary exchange. Immigration isn’t inherently a violation of anyone’s rights unless it involves trespassing on privately owned property. In a stateless society, there would be no arbitrary, government-imposed “borders,” only the boundaries of privately owned property. Immigration, then, would only be restricted by the ability of property owners to consent—or refuse—to allow others onto their land.

This framework ensures that movement and settlement are based on voluntary interactions and respect for property rights, rather than on coercive government policies. So, would a voluntarist society be “overrun” with immigrants? Not necessarily. It would simply shift the decision-making from arbitrary government lines to the consent of individual property owners.

Of course, the person need not be from Mars. He could be from Africa, Asia, or anywhere else. The point is that if he homesteads unowned land, he is the rightful owner under libertarian principles. This aligns with the idea of open borders because he hasn’t violated anyone’s property rights.

Now, the challenge with open borders arises when people come in who do violate others’ rights. Some might be murderers, or others might come from cultures where certain behaviors—like seeing a woman in a miniskirt—are interpreted as invitations to commit acts that are unacceptable in our society. Clearly, we want to keep those kinds of people out.

But then there’s another issue: what if there are a quadrillion Martians? Let’s say they’re all peaceful and wouldn’t harm anyone, but the sheer number of them would overwhelm our resources and infrastructure. How do we address that? How do we keep libertarian principles intact while also ensuring safety and practicality?

The answer is surprisingly simple: privatize every square inch of the country. Privatize the roads, the fields, the parks, the bodies of water—everything. In fact, I’ve written a book on this topic, Privatizing Oceans, Rivers, and Lakes. If all property is privately owned, then immigration is no longer about “open borders” in the traditional sense. It becomes about property rights. Anyone who enters without the consent of the property owner is trespassing, and private property owners can decide who is allowed on their land.

But this approach raises another issue: what about submarginal land? For example, vast areas in the middle of Alaska that nobody wants to homestead because it’s not economically viable right now. That land is effectively “open” because there’s no clear owner to enforce property rights. To address this, charitable organizations or private defense agencies could step in to homestead and manage those areas at a cost, safeguarding their clients and ensuring that trespassing is minimized.

This solution—open borders combined with private property rights—allows us to uphold libertarian principles while also ensuring safety and order. It eliminates the need for government-imposed restrictions, which violate libertarian theory, and replaces them with a voluntary, property-based system of decision-making.

The problem I have with limited or restricted borders is that, while their advocates are well-meaning and want to keep us safe, they compromise libertarian principles to achieve that goal. They sacrifice core libertarian theory by relying on state-enforced borders. I’m not willing to make that compromise. I want to keep libertarian theory intact and ensure safety.

On this issue, I have to say that Hans-Hermann Hoppe and even the later Murray Rothbard depart from pure libertarianism. By supporting state-imposed restrictions on immigration, they abandon the fundamental libertarian principle of voluntary interactions and property rights. I prefer a solution that preserves those principles while also addressing the legitimate concerns of safety and practicality.

Excellent. Final question for you. So in a stateless society, how would we protect ourselves from other countries that have states and that have armies? National defense be addressed in a voluntarist world?

Well, there is this country on the horn of Africa. I forget what the name of the country is. I’m so pathetic. What’s the one that they say it’s anarchy there? Somalia. Somalia. Good old Somalia. Thank you. I’m getting senile. I can’t remember.

Etienne:

Which is technically an anocracy. It’s not anarchy. It’s different factions fighting over the same government.

Walter Block:

So it’s not pure anarchy? Fine, it’s semi-anarchy. But let’s compare. If you stack Somalia against a developed country like Canada, sure, Somalia doesn’t look great. But if you compare Somalia to its neighboring countries, it starts to look a lot better. Why? Even in a semi-anarchic state, where there are contending factions or “gangs,” they’re capable of uniting when a common enemy appears. If Kenya tried to invade Somalia, for example, those factions would likely band together and kick Kenya’s butt.

Another example is Israel in 1948. At that time, there was no established IDF (Israeli Defense Forces) as we know it today. Instead, there were private groups like the Lehi, the Palmach, and the Irgun. Critics might call them “gangs,” but I’d call them private defense agencies. Despite being fragmented, they managed to defeat seven invading Arab armies. Seven armies! Without a centralized military force like the modern IDF, they still succeeded. So, don’t tell me that private defense agencies can’t handle national defense. History shows otherwise.

Now, of course, if China decided to invade a small place like Monaco or Liechtenstein—whether those places had governments or were purely anarchist—it wouldn’t be much of a contest. China has over a billion people, and Monaco has, what, 100,000? Numbers matter. But when comparing countries of roughly equal size and population, an anarchist society would be far wealthier than a statist one.

Why? Because free markets generate wealth. And as the saying goes, “Wealthier is healthier.” Well, wealthier is also safer. An anarchist U.S., with its free enterprise system fully unleashed, would be 20 times richer than countries like Russia or China. And if we were that much richer, they wouldn’t dare attack us. Superior wealth allows for superior defense capabilities.

So, the idea that anarchist systems can’t compete with governments in terms of safety, security, or war simply doesn’t hold up. History and economic logic suggest that a wealthy, decentralized society could not only defend itself but potentially outperform its statist rivals.

Perfect.

Hey, thank you so much for your time and contribution to Liberty the Rock’s Sedona 2024 The Voluntarism Conference.

It’s been a pleasure.

This has been Etienne de la Boétie from the Art of Liberty Foundation.

About Walter Block

Walter Block is the Harold E. Wirth Eminent Scholar Chair in Economics in the College of Business at Loyola University, New Orleans. He is a former Adjunct Scholar at the Mises Institute and the Hoover Institute. Block has previously taught at the University of Central Arkansas, Holy Cross College, Baruch (C.U.N.Y.) and Rutgers Universities. He earned a B.A. in philosophy from Brooklyn College (C.U.N.Y.) in 1964 and a Ph.D. degree in economics from Columbia University in 1972.

Walter Block is the author of over two dozen books. His most famous one, Defending the Undefendable (1976) – has been translated into over a dozen foreign languages. He has authored or co-authored Maturity Mismatching: Is this a legitimate banking practice? (2020), Property Rights: The Argument for Privatization (2019), Philosophy of Law: The Supreme Court’s Non- Use of Libertarian Law (2019), Space capitalism: the case for privatizing space travel and colonization (2019), An Austro-Libertarian Critique of Public Choice (2017), Essays in Austrian Economics (2017), Water Capitalism: The Case for Privatizing Oceans, Rivers, Lakes, and Aquifers (2015), Toward a Libertarian Society (2014), Legalize Blackmail (2013), Defending the Undefendable II (2013), Religion, Economics and Politics (2013), and Yes to Ron Paul and Liberty (2013).

Block has contributed over 600 articles and reviews to scholarly refereed journals and law reviews such as the Journal of Libertarian Studies, the Quarterly Journal of Austrian Economics, the Review of Austrian Economics, the American Journal of Economics and Sociology, the Journal of Labor Economics, Harvard Journal of Law and Public Policy and Public Choice. He has written several thousand op ed articles, newspaper columns, chapters in books, etc. He also gives numerous speeches to civic and educational institutions and appears regularly on television and radio.

About Liberty on the Rocks Conference & The Art of Liberty Foundation

Is the biggest secret in American/ international politics that “government” is illegitimate, immoral and completely unnecessary? Voluntaryism, REAL Freedom, is the only moral political philosophy on the market. Every other political “ISM” including socialism, communism and constitutional republicanism, has a ruling class that has rights that you don’t have, an illogical exception from morality, and “voting” is so easily rigged by monopoly media, moneyed interests, and the organized crime “government” itself counting the votes with unauditable black box voting machines and mail-in ballots that it is, frankly, a joke to think your vote matters or will even be counted.

The Art of Liberty Foundation, a start-up public policy organization exposing the illegitimacy and criminality of “government” from a principled voluntaryist perspective, is also educating the public on the 2nd biggest secret: We don’t really need “Government”! In a Voluntaryist world of REAL freedom, all the legitimate, non-redistributive services provided by monopoly “government” would be better provided by the free market, mutual aid societies, armed protective service companies, arbitration providers, insurance companies, non-profits and genuine charities. The world would be much more harmonious and prosperous under REAL freedom!

Liberty on the Rocks – Sedona – The Voluntaryism Conference

This year’s Liberty on the Rocks conference brought together some of the most respected economists, legal experts, political philosophers and academics to explain spontaneous order and how the free market would better provide everything from roads to military defense to air traffic control without the waste, fraud, abuse and extortion of monopoly “government.”

The foundation will be publishing Voluntaryism – How the Only “ISM” Fair for Everyone Leads to Harmony Properity and Good Karma for All! in the coming months where free excerpts have already begun appearing at ArtOfLiberty.Substack.com

Dr. Walter Block, the guy who WROTE THE BOOK on privatizing roads and highways, explains who would build the roads at The Voluntaryism Conference in Sedona.

In this, the 7th episode from Liberty on the Rocks – Sedona – The Voluntaryism Conference, renowned economist Dr. Walter Block delves into a classic libertarian question: “Without government, who will build the roads?” The transcript below is illustrated with memes and visualizations from Etienne de la Boetie 2’s upcoming book: Voluntaryism – How the Only “ISM” Fair for Everyone Leads to Harmony, Prosperity and Good Karma for All! Drawing on Dr. Block’s extensive research and insights from his book The Privatization of Roads and Highways, Dr. Block makes a compelling case for privatizing road infrastructure. He argues that private ownership can enhance safety, reduce traffic fatalities, and improve efficiency through competition and innovation. Highlighting both ethical and economic advantages, Block explains how privatization could alleviate traffic congestion and significantly lower the staggering 40,000 annual road fatalities in the U.S., which he attributes to government mismanagement. He also addresses common concerns, such as the risks of monopolies, accessibility issues, and national defense implications, offering creative, market-driven solutions for these challenges. With wit and thoughtful analysis, Dr. Block dismantles the assumption that only government can handle critical infrastructure, demonstrating how privatized roads could deliver a safer and more efficient alternative.’

Full Transcript

Etienne de la Boetie2 Introduction:

“But without government, who would build the roads?” This question has become something of a cliché in libertarian and voluntaryist circles, often used to highlight the unfortunate truth that many people rarely question the status quo or consider alternative ways society could function. The reality is that roads existed long before governments took charge of building and maintaining them—and, frankly, government management of roads has often been less than stellar. To help us explore this topic and answer the age-old question of who will build the roads and how, we are joined by a man who has, quite literally, written the book on the subject: Dr. Walter Block. Dr. Block is an esteemed economist, the former Harold E. Wirth Eminence Scholar Endowed Chair in Economics at the School of Business at Loyola University New Orleans, and a former senior fellow at the Ludwig von Mises Institute, a nonprofit think tank. With over two dozen books to his name, his most relevant work for today’s discussion is The Privatization of Roads and Highways: Human and Economic Factors. It is my pleasure to introduce Dr. Walter Block.

Walter Block: Thank you for the kind introduction, Etienne. However, I noticed you used the word former twice—one was accurate, and the other wasn’t. I’m not the former endowed chair at Loyola University; I’m actually the current one. But you were correct in stating that I’m the former senior fellow at the Mises Institute. I’m no longer associated with them—let’s just say we had a little disagreement over Israel.

That aside, I’m delighted to address your audience on the question of who would build the roads and how privatized roads would function. My overarching motto for privatization, whether it’s roads, highways, oceans, rivers, or even outer space, is this: If it moves, privatize it. If it doesn’t move, privatize it. Since everything either moves or doesn’t, the logical conclusion is that we privatize everything.

What’s the case for privatizing anything? There are two primary arguments. The first is efficiency. In a private system, if you do a good job, you can grow your business, expand your operations, and satisfy more customers. However, if you fail—if you consistently lose profits—you face the prospect of going bankrupt, forcing you to either improve or exit the market. This system of accountability ensures that inefficiency is weeded out over time. That’s why we generally have good-quality products in the private sector—pens, books, shirts, and countless other items. They’re not perfect, of course, because humans are inherently fallible and mistakes happen, but the private sector excels at delivering quality because of this built-in mechanism for improvement.

The second argument for privatization is rooted in ownership itself. Broadly, there are only three possibilities for ownership: privatization, government ownership, or non-ownership (what is often referred to as the tragedy of the commons). In the case of non-ownership, the lack of clear accountability leads to neglect and overuse. For instance, the reason we face problems like overfishing or the depletion of whale populations is because nobody truly owns the fish in the ocean. When something belongs to everyone, it effectively belongs to no one, and there’s little incentive to take proper care of it.

Non-ownership, or common ownership, presents significant problems. When everyone owns something, effectively no one does, which means no one takes proper care of it. This leads to issues like the tragedy of the commons, where resources—such as fish in the ocean or whales—are overexploited and depleted because no one has a vested interest in their sustainability.

Government ownership, on the other hand, is highly problematic from an ethical standpoint. Governments are inherently coercive institutions, and libertarians stand firmly against coercion. We advocate for voluntary interactions, not force, and the government embodies coercion in its very nature. That leaves private ownership as the only ethically legitimate option for managing resources and institutions.

It’s easy to see the case for privatizing certain things, like the post office or sanitation services. But what about highways, roads, and streets? This is where I’ll focus now.

The main argument for privatizing roads and highways is safety. Currently, around 40,000 people die every year on U.S. roads. Forty thousand lives lost annually—this is a staggering figure. For context, consider that approximately 3,000 people died in the 9/11 attacks, and around 1,900 people died during Hurricane Katrina in New Orleans, where I currently live. These were tragic events, yet the annual death toll on U.S. roads dwarfs them.

To further contextualize, let’s compare this to current events. According to reports from the Gaza Health Ministry (operated by Hamas), over 40,000 people have died in Gaza, and the world rightly recognizes this as a humanitarian catastrophe. Indeed, whenever 40,000 lives are lost, it is undeniably horrific. Yet, in the U.S., this same number of people dies every single year on the roads, along with hundreds of thousands suffering serious injuries. This ongoing tragedy deserves far more attention and demands a better solution.

Hopefully, the tragic events in the Middle East will be limited to one year, and peace will eventually prevail. But if the future resembles the past, the U.S. will continue to see 40,000 deaths on its highways every single year—and that’s absolutely horrific.

You’ve likely heard the saying: there are only two things in life that are inevitable—death and taxes. Well, while I’ll begrudgingly accept that death is inevitable, I don’t agree that taxes are. And I certainly refuse to accept that 40,000 highway deaths every year are inevitable.

So why are so many people dying on the roads? The answer lies in monopoly. Our roads are government-run, and monopolies inherently lack competition. Competition is what drives improvements in quality, safety, and innovation. Think about it—we have excellent pens, scissors, shirts, and even paperclips, all because businesses compete to provide the best products. But with highways, there’s no competition.

Take I-10, for example, the highway that runs through New Orleans and stretches from Florida to California. If it were privately owned and poorly managed, the owner would face financial losses, leading to a hostile takeover or the need for new ownership. Competition would ensure that someone else, someone better equipped to manage the highway, would step in. But with government ownership, there’s no such mechanism. Mismanagement persists because there’s no accountability or incentive to improve.

To illustrate this, consider McDonald’s—a massive global company. Not long ago, an incident occurred where McDonald’s was responsible for one death and injuries to 45 people. Now, McDonald’s is an enormous corporation selling billions of burgers, so they survived the backlash. But if something like that happened repeatedly, if McDonald’s killed 40,000 people annually, the company would cease to exist. Customers would abandon them, and they’d be replaced by competitors offering better and safer alternatives. This is the power of competition—a power we’re missing entirely when it comes to roads.

If McDonald’s failed us repeatedly, we’d simply go to Burger King, Wendy’s, or any other competitor. This highlights one key argument for privatization: competition leads to better outcomes. But my other major motivation for privatization is traffic congestion.

In many cities—New Orleans, where I now live, New York City, where I used to live, Seattle, where I visit often, and countless others, including cities in California—traffic congestion is a disaster. The average speed of traffic in these places is often slower than a bicycle, and sometimes even slower than a runner. A runner can manage about 12 miles per hour, while a walker might cover a mile in 20 minutes. Yet, drivers often find themselves stuck in bumper-to-bumper traffic, barely moving.

Take the Long Island Expressway, for example—infamously referred to as the “longest parking lot in the world.” Stretching around 100 miles, it frequently grinds to a standstill, leaving drivers just sitting there. This kind of gridlock is absurd and completely avoidable.

What’s the root cause of traffic congestion? Let’s break it down. Picture a basic supply-and-demand chart: on one axis, you have quantity, and on the other, price. The demand curve intersects with the supply curve to determine the price. Now, what’s the price you pay to use roads like the Long Island Expressway, I-10, I-5, or I-95? Zero. You don’t pay anything at the moment you use the road because you’ve already paid—through taxes, income taxes, or gasoline taxes.

This zero-price system means there’s no immediate cost to using the highway, so there’s no mechanism to regulate demand. Everyone piles onto the road at the same time, creating congestion. It’s a classic case of economic mismanagement.

What we’re dealing with here is basic supply and demand. When the amount of road space supplied falls short of the amount demanded, we end up with a shortage—and that’s all a traffic jam is: a shortage of available road capacity. It’s a simple concept rooted in economics, yet it’s something we constantly experience on government-run roads.

Apologies for the technical hiccups—I’m not great with whiteboards, but I think I’ve sorted that out now. Let’s move on.

My two main motivations for privatizing roads are straightforward. First, the shocking loss of life: 40,000 people die on U.S. highways every year. That’s a staggering number, and chances are that everyone listening to this either knows someone—or knows someone who knows someone—who has died or been seriously injured on the roads. It’s a national tragedy, yet it’s rarely discussed in the media. Think about it—when Hurricane Katrina hit or the 9/11 attacks occurred, the news was dominated by those events, as it should have been. But 40,000 highway deaths occur every single year, and it’s largely ignored.

The second major issue is traffic congestion, which I’ve already touched on. But now let’s ask: how could private ownership of roads make things better?

For one, private roads would likely handle speed limits differently. On government roads today, there are arbitrary speed regulations. For example, highways often have a minimum speed limit of 40 mph and a maximum of 70 mph. If you can’t go at least 40 mph, you’re not allowed on the highway, and if you exceed 70, you’re technically breaking the law. However, enforcement is inconsistent. Drivers routinely go 75, 80, or even higher without receiving tickets—unless they’re unlucky or the police officer is in a bad mood that day.

Now consider the left lane, which is meant for faster traffic. If you’re driving 70 mph in the left lane, you’ll often find cars overtaking you in the middle lane. At night, drivers will flash their high beams at you, honk, or otherwise signal that they think you’re a “clod” or a “moron” for blocking the faster lane. Although there are occasional signs advising slower cars to stay in the right lane, enforcement is virtually nonexistent. You could drive 65 mph in the left lane, frustrating everyone else, and you’d almost never get a ticket. This lack of clear rules and enforcement creates chaos and inefficiency on the roads.

Private ownership could address this. A private road owner has an incentive to set rules that maximize safety, efficiency, and customer satisfaction. If they fail to manage their roads effectively, they lose business or face competition. This kind of accountability is absent in government-run road systems, and the consequences are both deadly and frustrating for drivers.

Okay, let me pull up the screen again and ask you all a question. Imagine we have three lanes: the left lane, the middle lane, and the right lane. Now, suppose I own a road and implement this rule: everyone in the left lane must drive 60 miles per hour, everyone in the middle lane must drive 70, and everyone in the right lane must drive 85. No deviations—no 65, no 75, no odd speeds. The question is: would this save lives?

The honest answer is, we don’t know. Maybe this system would save lives. Or maybe the limits should be lower—say 55, 70, and 85. But again, we just don’t know. And that’s the issue.

In other industries, we can experiment and learn what works best. For example, people make shirts, scissors, pens, and even rabbits in all sorts of ways. (Yes, rabbits—don’t ask me why I mentioned rabbits, but stick with me here.) Some methods are better than others, and through trial and error, we learn which approaches are most effective. But when it comes to roads, we don’t have the freedom to experiment because Washington, D.C., mandates the rules. The government says the minimum is 40 mph, the maximum is 70 mph—and that’s it. There’s no room for innovation.

Let’s try another idea. Here’s a new whiteboard. Again, we have three lanes: left, middle, and right. Suppose we created a rule where, if someone passes you on the middle lane while you’re driving in the left lane, you automatically get a ticket. Would that work?

Honestly, I don’t know. Nobody knows. My theory is that the more lane-switching there is, the more accidents and deaths occur. So, if we had a system where everyone drove a specific speed in a specific lane, it might reduce lane switching and, in turn, reduce fatalities.

But again, I don’t claim to be a road safety expert. What I do know is that under private ownership, road owners would have the incentive to experiment, innovate, and figure out what systems work best to maximize safety and efficiency. That’s something we’re simply not getting with government-run roads.

What do I know about roads? Not much, I admit. There are people who are road experts—engineers who go to school and study these things. Unfortunately, in those schools, they rarely, if ever, teach about private roads or alternative ways of managing roadways. But here’s something I posit, something I hypothesize: lane changing is dangerous. Obviously, some lane changing is unavoidable, but if we could minimize it, maybe we’d save lives. I don’t know for sure—but the problem is that no one knows. And the current system, with government-run roads, isn’t set up to allow us to find out.

Let me try another example. Imagine a two-lane highway, with both lanes going in the same direction. Here’s one truck in the right lane, and here’s another truck right behind it. (Apologies for my drawing—no, I’m not drunk, I’m just not great at drawing rectangles on a screen.) Now, when I see one truck following another like this, I know what’s going to happen: the rear truck is going to try to pass the first truck. And it’s going to take forever—maybe 15 miles—for this truck to creep past the other. It’s like watching a slow-motion race.

What do I do in this situation? Well, I hate to admit it—and I hope no police officers are listening—but I’ll step on the gas and try to pass both trucks before they block me in. It’s risky, I know. I shouldn’t be speeding, and I definitely shouldn’t be speeding more just to avoid trucks. But what else can I do?

Maybe we need a system where the slower truck gets a ticket for not letting the faster truck pass. I’m not sure of the exact solution, but I do know that this kind of problem happens all the time, and I’ve never seen a cop pull over a truck for blocking a faster vehicle. These are just some of the issues that private roads might address—and possibly solve—in innovative ways.

Here’s another idea. If I owned a highway—let’s call it the Walter Highway—one thing I’d do to reduce accidents is install highly visible warnings in dangerous areas. For example, whenever there’s a part of the road where many deaths have occurred, I’d put up a large marker—a Christian cross, a Star of David, an Islamic crescent, or another symbol—depending on the individual involved. These markers wouldn’t be small. They’d be 50 or even 100 feet tall to make them impossible to ignore. The idea is to scare people into driving more carefully by visually reinforcing the dangers of that section of road. Maybe the road tilts, maybe it’s poorly lit, or maybe it has sharp curves—but whatever the reason, these markers would help alert drivers to areas where caution is needed.